By Karl Zinsmeister

Editor’s note: The following is adapted from a talk delivered on January 29, 2016, at Hillsdale College’s Allan P. Kirby, Jr. Center for Constitutional Studies and Citizenship in Washington, D.C. The opinions expressed in Imprimis are not necessarily the views of Hillsdale College.

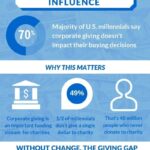

Private philanthropy is crucial in making America the unusual country that it is. Let’s start with some numbers. Our nonprofit sector now comprises eleven percent of the total United States workforce. It will contribute around six percent of gross domestic product this year. To put this in perspective, the charitable sector passed the national defense sector in size in 1993, and it continues to grow. And these numbers don’t take volunteering into account: charitable volunteers make up the equivalent — depending on how you count — of between four and ten million full-time employees. So philanthropy is clearly a huge force in our society.

To begin to understand this crucial part of America, it is useful — and also inspiring — to consider some of America’s great philanthropists.

Ned McIlhenny, born and raised in a Louisiana bayou, had a day job in addition to being a philanthropist: manufacturing and selling the hot pepper condiment invented by his family, McIlhenny Tabasco. There is big money in helping people burn their tongues, and McIlhenny used his resulting fortune for an array of good works. I’ll give you just one example. When he was young, hats with egret plumes were all the rage for ladies — like Coach handbags today — with the effect that the snowy egret, a magnificent creature native to Louisiana’s bayous, had become nearly extinct. In response, McIlhenny beat the bushes to find eight baby egrets on a private island his family owned. By 1911, he built up a population of 100,000 egrets on the island. At the same time, he convinced John D. Rockefeller and other philanthropists to help him purchase some swampy land to use as a winter refuge for egrets and other birds.