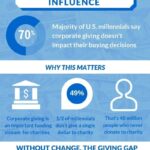

These days, we have high expectations of what companies should be. It’s not enough that they make good products. They also need to be good citizens. We expect them to minimize their social and environmental harm, to report their “impacts,” and to give money to charity. And we expect them to do more than simply follow the law. In 1970, the economist Milton Friedman said businesses should think only about making profit (any idea of social responsibility was a distraction and a disservice to shareholders, he wrote). But in the 21st century we’re starting to demand even more: Companies need to solve problems and aid causes, whether it’s Coca-Cola’s diarrhea program in Africa or Pampers’ one-for-one vaccine campaign with Unicef.

Porter’s Shared Value Initiative looks at how companies can make profits by catering to the need for things like water, sanitation, and economic opportunity. It argues that social causes are sources of competitive advantage, particularly in the developing world, and that socially focused business rebrands what companies are about. Porter says companies have allowed themselves to be portrayed as parasitic and unfeeling toward society, when in fact there’s enormous good that capitalism can do, properly executed.

The notion of companies delivering social value as an explicit goal is a radical one. It takes commerce beyond Friedman’s maxim, and beyond the defensiveness of corporate social responsibility. It embraces positivity and action, and allows profits to be linked to economies that won’t improve unless people’s lives improve. In the absence of government action, companies have a role in fixing social problems (water, electricity, lighting)—much the better to build local markets. The trick for multinationals—as a string of “impact startups” is showing—is to create “appropriate” technology, at appropriate prices.