By Jee Kim, Ford Foundation

Philanthropy, in its current institutional form, is only about a century old. Since its inception, both donors and the larger public have debated how individuals can deploy their accumulated wealth to serve the greater good. In fact, the discussion of institutional philanthropy’s role in society, and its relationship to government and markets, was much more heated during the early 20th century. In 1910, when John D. Rockefeller attempted to obtain a federal charter to establish his foundation, Congress turned him down. (He had more success with the New York State Legislature, which granted him a state charter in 1913.) In 1912, the Commission on Industrial Relations recommended that the Rockefeller Foundation be regulated or shut down entirely, arguing that “the domination by the men in whose hands the final control of a large part of American industry rests is not limited to their employees, but is being rapidly extended to control the education and ‘social service’ of the Nation.”

Over 100 years later, the field of philanthropy still wrestles with these important questions, debating the legal frameworks and tax regimes that govern foundations; the diversity of their boards and staff; their democracy in decision-making; and the alignment of their endowments with their program values and goals. In our current Gilded Age, marked by the accumulation of vast fortunes and a new generation of donors who occupy increasingly significant positions in civil society, it’s no coincidence that the big questions about philanthropy’s appropriate role are being rekindled. As Gara LaMarche asks in his online journal Democracy: “Why are we…hypersensitive to the dangers of big money in politics…but blind, it seems, to the dangers of big philanthropy in the public sphere?”

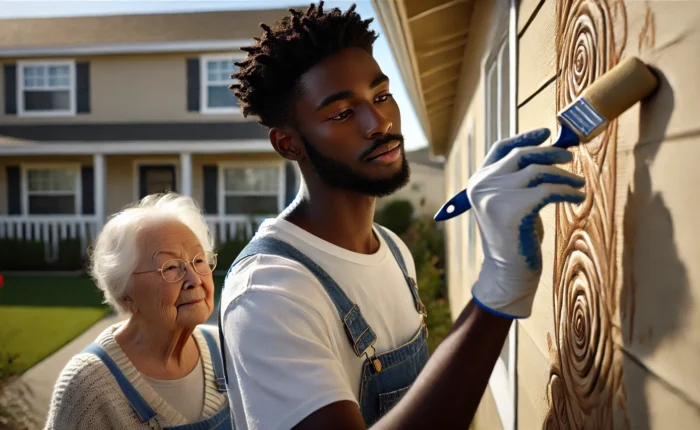

Part of the complexity of today’s philanthropy owes to the fact that wealth is being created more quickly than ever through developments in technology, and yet remains concentrated in the hands of a few. Whereas a previous era’s wealth was created through oil and steel, today’s is being amassed through data and software. And though we seem to have entered a virtual world, its effects are extremely physical. While a new generation of entrepreneurs has significantly democratized access to knowledge and information, it has also concentrated the resulting wealth into a few hands, predominantly male and overwhelmingly white. Companies like Apple make use of tax havens, even as inequality remains on the rise. The new social-media platforms created by the tech industry have been used by movements ranging from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter—and yet children as young as 7 are mining cobalt for smartphone batteries, and families from diverse backgrounds are being pushed out of their homes in cities like San Francisco, where the tech industry has taken over. Can philanthropy do enough to redress these inequalities—or is there something more fundamental at stake?

In “The Gospel of Wealth,” written in 1889 as a manifesto of sorts for the beneficiaries of the first Gilded Age, Andrew Carnegie describes massive inequality as the unavoidable consequence of a free-market system and suggests that philanthropy would ease the pressures created by it.