by Theodore Dalrymple

A lengthy paper in the Journal of Economic Psychology (54 (2016) 64 – 84), lyrically titled ‘“… Do it with joy!” — Subjective well-being outcomes of working in non-profit organisations’ — tries to demonstrate that British workers in the so-called third sector — that is to say, non-profit organisations — derive considerably more life satisfaction than those who work in the for-profit sector. The author, Dr Martin Binder, of Bard College in Berlin, concludes:

This paper has explored the impact of non-profit work on life satisfaction and found a significant and positive impact (the size about more than a fourth of that of getting widowed).

This is a rather peculiar statement, which does not tell us whether widowhood’s effect is positive or negative. If positive, is it an implicit plea that disgruntled wives should be supplied with poison at public expense for the sake of their well-being?

The author compared the life satisfaction according to various self-report measures of well-being of 12,786 employees in private firms and 966 employees in non-profit organisations. He found the life satisfaction of the latter to be greater than that of the former, even though their salaries were, on average, lower.

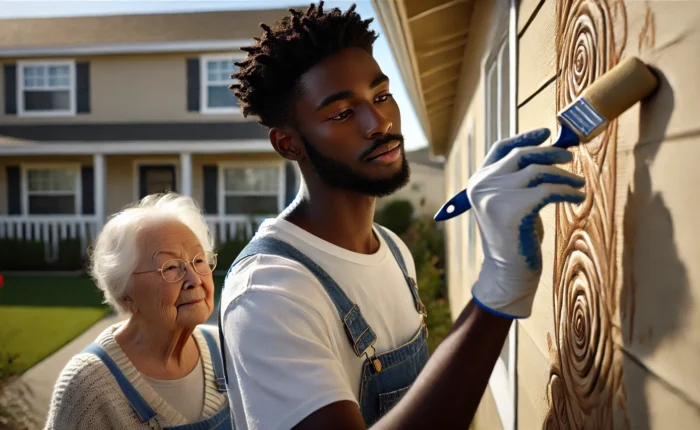

In the discussion of the results, arrived at after a heroic amount of statistical calculation, he suggests that this may be because those in the non-profit sector feel that they are doing something socially useful. He admits that he has proved no causative relationship — it could be, for example, that pre-existing differences in personality accounted for the superior contentment of the workers in the non-profit sector — but he does not favour this explanation. Of course, it is also possible that that there was no causative relation in either direction.

His results are consistent with the proposition that self-satisfaction is good for you. The workers in the non-profit sector derive satisfaction from the idea that they are doing something worthwhile, something good. There is no requirement in that feeling of satisfaction that they should actually be doing good. I have no doubt that workers for UNICEF felt very pleased with their work, bringing wells to the villages of Bangladesh, work that resulted in the largest mass poisoning (with arsenic) in history. Nor is it difficult to show that many large charities in Britain are charitable only in the legal and accounting sense, which is different from that of common usage. I asked the old ladies serving in a charity shop in my town what proportion of the money they took they thought went to the charity in whose name the shop was run.